BY MITCH STOLTZSEPTEMBER 19, 2018

Update: The revised Music Modernization Act passed by the Senate has been signed into law as the Hatch-Goodlatte Music Modernization Act.

The Senate passed a new version of the Music Modernization Act (MMA) as an amendment to another bill this week, a marked improvement over the version passed by the House of Representatives earlier in the year. This version contains a new compromise amendment that could preserve early sound recordings and increase public access to them.

Until recently, the MMA (formerly known as the CLASSICS Act) was looking like the major record labels’ latest grab for perpetual control over twentieth-century culture. The House of Representatives passed a bill that would have given the major labels—the copyright holders for most recorded music before 1972—broad new rights in those recordings, ones lasting all the way until 2067. Copyright in these pre-1972 recordings, already set to last far longer than even the grossly extended copyright terms that apply to other creative works, would a) grow to include a new right to control public performances like digital streaming; b) be backed by copyright’s draconian penalty regime; and c) be without many of the user protections and limitations that apply to other works.

Second, the public found a champion in Senator Ron Wyden, who proposed a better alternative in the ACCESS to Recordings Act. Instead of layering bits of federal copyright law on top of the patchwork of state laws that govern pre-1972 recordings, ACCESS would have brought these recordings completely under federal law, with all of the rights and limitations that apply to other creative works. While that still would have brought them under the long-lasting and otherwise deeply-flawed copyright system we have, at least there would be consistency. Two things changed the narrative. First, a broad swath of affected groups spoke up and demanded to be heard. Tireless efforts by library groups, music libraries, archives, copyright scholars, entrepreneurs, and music fans made sure that the problems with MMA were made known, even after it sailed to near-unanimous passage in the House. You contacted your Senators to let them know the House bill was unacceptable to you, and that made a big difference.

Weeks of negotiation led to this week’s compromise. The new “Classics Protection and Access Act” section of MMA clears away most of the varied and uncertain state laws governing pre-1972 recordings, and in their place applies nearly all of the federal copyright law. Copyright holders—again, mainly record labels—gain a new digital performance right equivalent to the one that already applies to recent recordings streamed over the Internet or satellite radio. But older recordings will also get the full set of public rights and protections that apply to other creative work. Fair use, the first sale doctrine, and protections for libraries and educators will apply explicitly. That’s important, because many state copyright laws—California’s, for example—don’t contain explicit fair use or first sale defences.

The new bill also brings older recordings into the public domain sooner. Recordings made before 1923 will exit from all copyright protection after a 3-year grace period. Recordings made from 1923 to 1956 will enter the public domain over the next several decades. And recordings from 1957 onward will continue under copyright until 2067, as before. These terms are still ridiculously long—up to 110 years from first publication, which is longer than any other U.S. copyright. But our musical heritage will leave the exclusive control of the major record labels sooner than it would have otherwise.

The bill also contains an “orphan works”-style provision that could allow for more use of old recordings even if the rightsholder can’t be found. By filing a notice with the copyright office, anyone can use a pre-1972 recording for non-commercial purposes, after checking first to make sure the recording isn’t in commercial use. The rightsholder then has 90 days to object. And if they do, the potential user can still argue that their use is fair. This provision will be an important test case for solving the broader orphan works problem.

The MMA still has many problems. With the compromise, the bill becomes even more complex, extending to 186 pages. And fundamentally, Congress should not be adding new rights in works created decades ago. Copyright law is about building incentives for new creativity, enriching the public. Adding new rights to old recordings doesn’t create any incentives for new creativity. And copyrights as a whole, including sound recording copyrights, still last for far too long.

Still, this compromise gives us reason for hope. Music fans, non-commercial users, and the broader public have a voice—a voice that was heard—in shaping copyright law as long as legislators will listen and act.

An online collection of links, articles and websites relevant to the teaching of Media and Cinema Studies in the 21st Century. Designed with the needs of the contemporary student in mind, this blog is intended to be a resource for teachers and students of the media alike.

Showing posts with label Law. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Law. Show all posts

Thursday, 1 November 2018

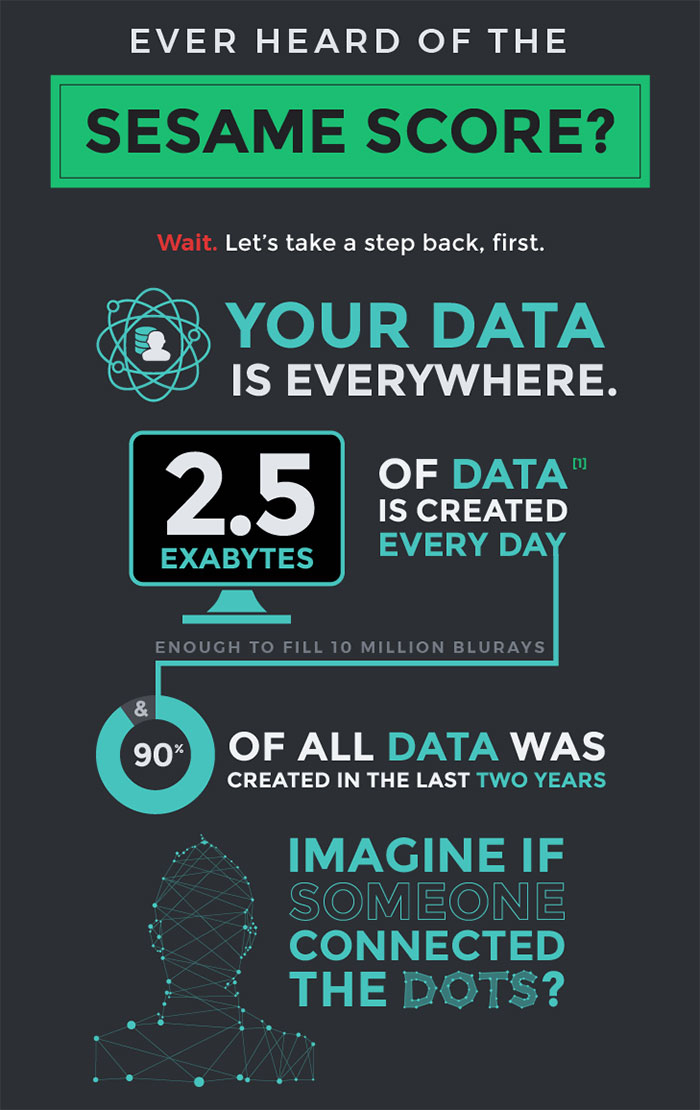

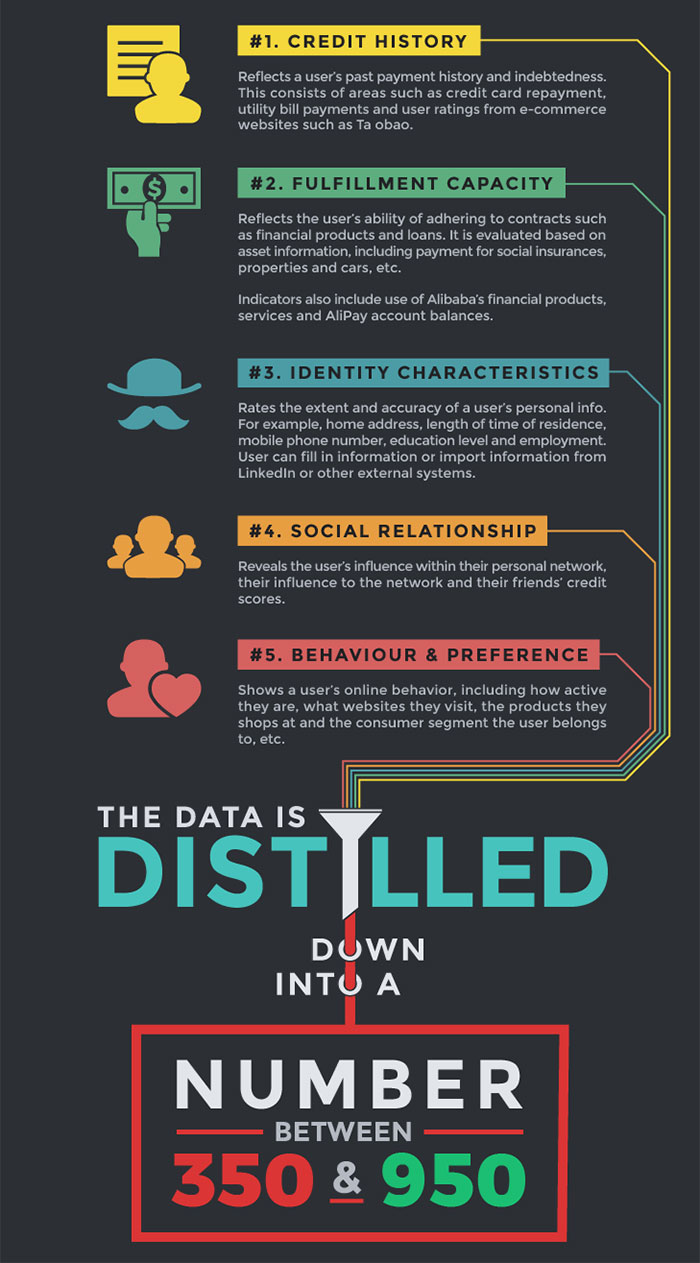

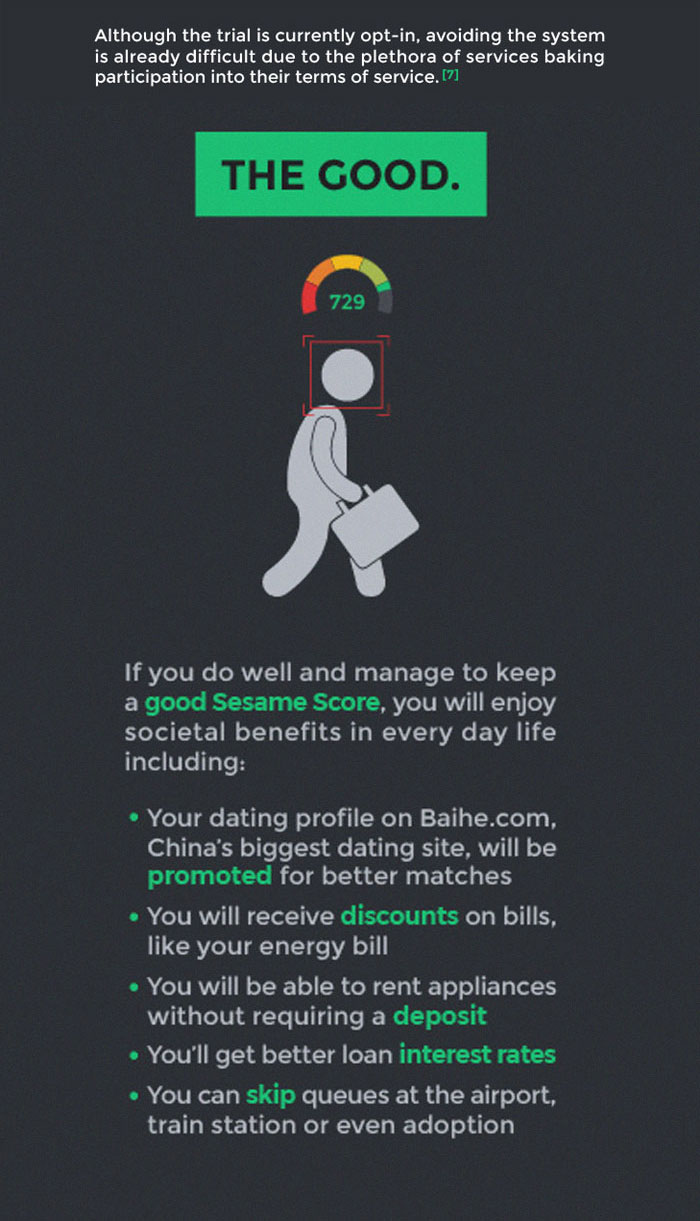

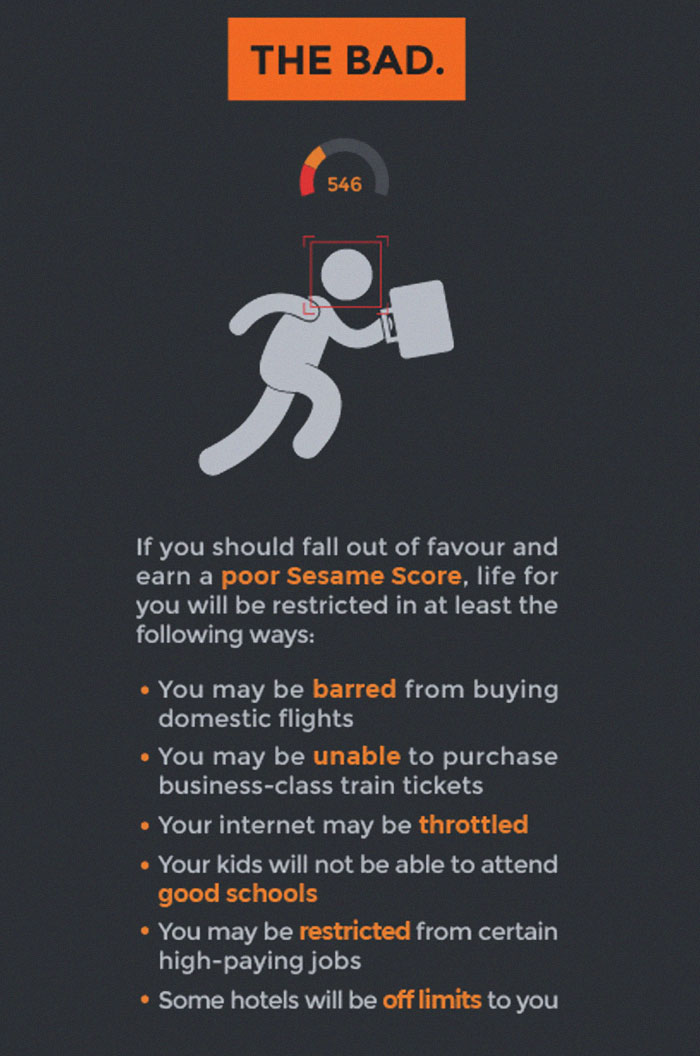

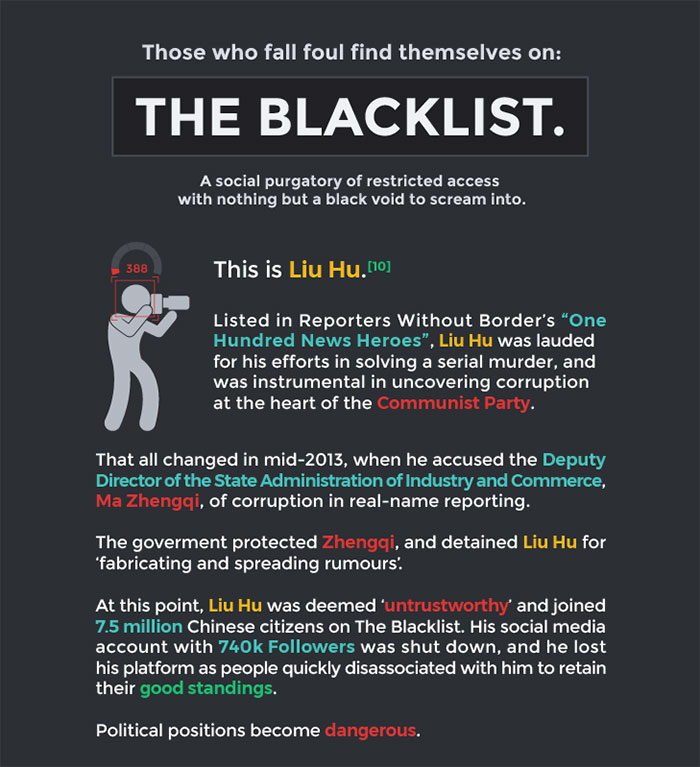

Here’s How China’s ‘Social Credit Score’ Punish And Reward Citizens, And It’s Terrifying

By Josh Reynolds

George Orwell’s 1984, Black Mirror S03E01, Psycho Pass, The Orville and many others have all theorised how technology can make our lives better… or worse.

The future is now.

More info: imgur.com

Thursday, 13 September 2018

How Australia’s Proposed Surveillance Laws Will Break The Trust Tech Depends On

In the last few years, we’ve discovered just how much trust - whether we like it or not - we have all been obliged to place in modern technology. Third-party software, of unknown composition and security, runs on everything around us: from the phones we carry around, to the smart devices with microphones and cameras in our homes and offices, to voting machines, to critical infrastructure. The insecurity of much of that technology, and increasingly discomforting motives of the tech giants that control it from afar, has rightly shaken many of us.

But the latest challenge to our collective security comes not from Facebook or Google or Russian hackers or Cambridge Analytica: it comes from the Australian government. Their new proposed “Access and Assistance” bill would require the operators of all of that technology to comply with broad and secret government orders, free from liability, and hidden from independent oversight. Software could be rewritten to spy on end-users; websites re-engineered to deliver spyware. Our technology would have to serve two masters: their customers, and what a broad array of Australian government departments decides are the “interests of Australia’s national security.” Australia would not be the last to demand these powers: a long line of countries are waiting to demand the same kind of “assistance.”

In fact, Australia is not the first nation to think of granting itself such powers, even in the West. In 2016, the British government took advantage of the country’s political chaos at the time to push through, largely untouched, the first post-Snowden law that expanded not contracted Western domestic spying powers. At the time, EFF warned of its dangers —- particularly orders called “technical capability notices”, which could allow the UK to demand modifications to tech companies’ hardware, software, and services to deliver spyware or place backdoors in secure communications systems. These notices would remain secret from the public.

Last year we predicted that the other members of Five Eyes (the intelligence-sharing coalition of Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) might take the UK law as a template for their own proposals, and that Britain “… will certainly be joined by Australia” in proposing IPA-like powers.

That’s now happened. This month, in the midst of a similar period of domestic political chaos, the Australian government introduced their proposal for the “Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Bill 2018.” The bill unashamedly lifts its terminology and intent from the British law.

But if the Australian law has taken elements of the British bill, it has also whittled them into a far sharper tool. The UK bill created a hodge-podge of new powers; Australia’s bill recognizes the key new powers in the IPA and has zeroed in on their key abilities: those of assistance and access.

If this bill passes, Australia will - like the UK - be able to demand complete assistance in conducting surveillance and planting spyware, from a vast slice of the Internet tech sector and beyond. Rather than having to come up with ways to undermine the increasing security of the Net, Australia can now simply demand that the creators or maintainers of that technology re-engineer it as they ask.

It’s worth underlining here just how sweeping such a power is. To give one example: our smartphones are a mass of sensors. They have microphones and cameras, GPS locators, fingerprint and facial scanners. The behaviour of those sensors is only loosely tied to what their user interfaces tell us.

Australia seeks to give its law enforcement, border and intelligence services, the power to order the creators and maintainers of those tools to do “acts and things” to protect “the interests of Australia’s national security, the interests of Australia’s foreign relations or the interests of Australia’s national economic well-being”.

The “acts and things” are largely unspecified - but they include enabling surveillance, hacking into computers, and remotely pulling data from private computers and public networks.

The range of people who would have to secretly comply with these orders is vast. The orders can be served on any “designated communications provider”, which includes telcos and ISPs, but is also defined to include a “person [who] develops, supplies or updates software used, for use, or likely to be used, in connection with: (a) a listed carriage service; or (b) an electronic service that has one or more end users in Australia”; or a “person [who] manufactures or supplies customer equipment for use, or likely to be used, in Australia”.

Examples of electronic services may “include websites and chat fora, secure messaging applications, hosting services including cloud and web hosting, peer-to-peer sharing platforms and email distribution lists, and others.”

You can see the full list in the draft bill in section 317C, page 16.

As Mark Nottingham, co-chair of the IETF’s HTTP group and member of the Internet Architecture Board, notes, this seems to include “Everyone who’s ever written an app or hosted a Web site - worldwide, since one Australian user is the trigger - is a potential recipient, whether they’re a multimillion dollar company or a hobbyist.” It includes Debian ftpmasters, and Linux developers; Mozilla or Microsoft; certificate authorities like Let’s Encrypt, or DNS providers.

This is not an error: when we were critiquing a similarly broad definition in the UK’s IPA, we pointed out that the wording would allow the authorities to target a particular developer at a company (while requiring them to not inform their boss), or non-technical bystander who would not know the impact of what they were being asked to do. Commentators from close to GCHQ denied this would be the case and said that this would be clarified in later documents - but subsequent draft codes of practice actually doubled down on the breadth of the orders, saying that it was deliberately broad, and that even café owners who operated a wifi hotspot could be served with an order.

There are some signs that the companies affected by these orders have learned the lesson of the IPA, and pushed back during the Assistance and Access’s preliminary stages. Unlike the UK bill, there are clauses forbidding Australia from being required to “implement or build [a] systemic weakness or systemic vulnerability into a form of electronic protection” (S.317ZG); and preventing actions in some cases that would cause material loss to others lawfully using a targeted computer (e.g. S.199 (3), pg 163. Companies have an opportunity to be paid for their troubles, and billing departments can’t be targeted. There is some attempt to prevent government agencies forcing providers to “make false or misleading statements or engage in dishonest conduct”(S.317E).

But these are tiny exceptions in a sea of permissions, and easily circumvented. You may not have to make false statements, but if you “disclose information”, the penalty is five years’ imprisonment (S.317ZF). What is a “systemic weakness” is determined entirely by the government. There is no independent judicial oversight. Even counselling an ISP or telco to not comply with an assistance or capability order is a civil offence.

If the passage of the UK surveillance law is any guide, Australian officials will insist that while the language is broad, no harm is intended, and the more reasonable, narrower interpretations were meant. But none of those protestations will result in amendments to the law: because Australia, like Britain, wants the luxury of broad, and secret powers. There will be - and can be no true oversight - and the kind of malpractice we have seen in the surveillance programs of the U.S. and U.K. intelligence services will spread to Australia’s law enforcement. Trust and security in the Australian corner of the Internet will diminish - and other countries will follow the lead of the anglophone nations in demanding full and secret control over the technology, the personal data, and the individual innovators of the Internet.

“The government,” says Australia’s Department of Home Affairs web site, “welcomes your feedback” on the bill. Comments are due by September 10th. If you are affected by this law - and you almost certainly are - you should read the bill, and write to the Australian government to rethink this disastrous proposal. We need more trust and security in the future of the Internet, not less. This is a bill that will breed digital distrust, and undermine the security of us all.

Saturday, 16 September 2017

Media laws: Who will buy what and will it make any difference anyway?

Via abc.net.au/news/2017-09-15/australian-media/8949574 By business reporter Stephen Letts Updated 16 September 2017

As the new media laws finally clambered over their last obstacle, you could almost hear the high-fives slapping in the boardrooms of the big — although somewhat diminished — media companies.

Key points:

- Fairfax and Nine appears to be the most plausible and powerful merger opportunity

- News Corp's main hurdle to any acquisition is likely to be the ACCC

- Even after merging most businesses would still struggle to grow sales in the face of massive competition from overseas digital giants

The denouement of the drawn-out and fraught process, televised on the Senate channel, had more the torn and frayed look of the Survivor franchise than the smoochy fairytale feel of The Bachelor, which aired around the same time.

So now the rule book has been rewritten, how is the game going to change? And is the promise of mergers and takeovers of struggling media businesses going to create new champions able to protect and expand their turf?

Certainly, the prospect of mergers is real — if for no other reason than: why did the media owners champion the changes in media ownership rules? Will they be successful? That is an entirely different question.

So now the rule book has been rewritten, how is the game going to change? And is the promise of mergers and takeovers of struggling media businesses going to create new champions able to protect and expand their turf?

Certainly, the prospect of mergers is real — if for no other reason than: why did the media owners champion the changes in media ownership rules? Will they be successful? That is an entirely different question.

What are the new rules?

It was not so much a rewriting of the Broadcasting Legislation Amendment Bill as just hitting delete on a couple of key provisions that changed things. Out went the "75 per cent audience reach" rule prohibiting a TV network broadcasting to more than 75 per cent of the population. It opens up possibilities for the likes of Seven, Nine, Ten and the regional players Prime, Southern Cross and WIN.The removal of "two-from-three" rule — owning any two of TV, print and radio was OK, owning all three was not — is the one that puts everybody into play. There are also bits like replacing TV and radio licence fees with a "spectrum fee", although they are unlikely to make much difference to the flow of deals in the wings. However, that doesn't mean it is total open slather — some checks remain.

The "five/four rule" enshrined by the Howard government in 2007 to prevent the number of media owners falling below five in capital cities and four in regional areas, is still on the books, while the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission — with its own rule book — is still on the prowl looking to bust market domination. To lesser extent, the Foreign Investment Review Board and shareholders themselves are in the mix, but they have never really been known to stop media takeovers.

A couple of times, shareholders have tried to stand in the way of a merger — to wit, a body of West Australian Newspaper investors against Kerry Stokes in 2011 and Ten investors at the moment — but they have generally been run over in the process.

Here are the most likely deals

The big investment bank, Morgan Stanley, has tallied up the permutations and combinations flowing from the law changes and has come up the most likely deals. There are a fair few options, but for the sake of brevity, this is the short list of the bigger deals being discussed:- Nine Entertainment and Southern Cross;

- Fairfax Media and Nine;

- Seven West Media and Prime Media;

- News Corporation and just about anyone.

So Fairfax and Nine? Far more plausible and powerful, according to Mr McLeod. "This could be a rare opportunity to combine media assets and actually lift revenue growth rates via the two online businesses," he said. "Nine's video content could strengthen Fairfax's online video capability and lift traffic and audiences for the Fairfax sites."

Importantly, Mr McLeod notes both companies have little or no debt, which is a big advantage in delivering a highly positive earning per share outcome to both sets of investors.

Seven has always been regarded as a natural predator for its regional partner Prime and now the reach rule has been removed, it is off the leash. Given Prime is a reseller of Seven content, no-one else is likely to bid for it. Does it make sense for Seven? Sort of, but Prime is a lean operation and the cost savings in merging the two may not be large enough to make it worthwhile, and the potential for ongoing earnings growth is minimal.

News Corp is the $10b gorilla

Talking about off the leash, News Corp has never been shy about buying businesses — good, bad or indifferent, profitable or unprofitable — it just buys them and considers the consequences and write-downs later.Last month, it wrote down the value of sundry newspapers, its stake in Foxtel and the REA real estate portal by $1.3 billion. Although that is dwarfed by the impairments News Corp has racked up by buying the likes of Dow Jones and Gemstar over the years. With its US rival CBS likely to snaffle Ten, News Corp could well turn its attention to Nine or Seven.

News already owns plenty of assets here and so any deal could be quite cost-effective or nerve-racking, depending on whether you are a shareholder or work in a newsroom facing further "rationalisation". The merger of online businesses and picking up Nine or Seven video content would be handy for News Corp's digital platforms.

Of course, any move from News while OK under the new media laws would still need to leap any hurdle put in its way by the ACCC. News could always satisfy itself with a tasty morsel like the $700 million Here, There & Everywhere radio network owner of brands such as KIIS and Gold, as well as the Adshel outdoor advertising business.

Player

|

Earnings (2018 estimates)

|

Market capitalisation

|

News Corporation

|

$1.135b

|

$10b

|

Seven West Media

|

$208m

|

$1.1b

|

Nine Entertainment

|

$206m

|

$1.2b

|

Fairfax Media

|

$268m

|

$2.2b

|

Southern Cross

|

$171m

|

$1b

|

Here, There & Everywhere

|

$120m

|

$700m

|

Prime Media

|

$53m

|

$100m

|

Earnings based on Morgan Stanley estimates of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA).

What does history teach us?

The last significant media law changes in 2006 — largely centred on abolishing foreign ownership rules — certainly arced up deal making, both large and small. It also sparked activity not held back by foreign ownership issues.The then-Packer vehicle PBL sold half its media assets to the foreign private equity business CVC, proving you can have more than Alan Bond in your life. Kerry Stokes also hooked up with private equity, this time Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts selling it a 50 per cent stake in his media assets including Seven and the magazine business for $3.2 billion. They are worth about a third of that today. That deal allowed a cashed-up Mr Stokes to get a large foothold in, and ultimately control of, his hometown West Australian Newspapers. Fairfax headed bush and bought Rural Press.

Morgan Stanley's Andrew McLeod says the experience of 2006 shows transactions could occur very quickly in 2017. "Some of the remaining ownership rules, such as the 'five/four minimum voices' rule, present a first-mover advantage for consolidation occurring in some assets and some markets," he said.

So can the mergers turn back the tide?

The bigger question is whether any of this will create more robust businesses able to compete and grow against the likes of Facebook and Google in the ad market.Unlike King Canute of yore, who stood in front of a tide to prove his fallibility knowing such things were beyond mere mortals, the Government is backing its plan to help turn back the digital tsunami crashing in from offshore and sweeping away local profits.

Good luck with that, says Mr McLeod. "We think the key debate is whether on the other side of any merger and acquisition, higher growth/better quality media companies emerge — or if after one year's costs savings are banked, the downward trajectory in earnings and shareholder value resumes," he said. "We can envisage a few genuine re-invention opportunities, but in most cases it's more likely the latter."

Crushed: Digital giants vs Australian media

Last year Australian TV networks lost around $1 billion between them, newspapers have lost even more over recent years, while profitability in radio is flat-lining at best. The test will be to achieve real top-line growth in sales, not just confected and unsustainable profit growth from cost-cutting.The problem there is the advertising revenue pool is a bit of a zero sum game — with some GDP-style growth added in. In such a relatively stagnant pool, gaining sales means someone is losing. And on an exponential scale, the digital giants are winning and everyone else is losing. The one thing the likes of Facebook and Google won't do is bail out Australian shareholders with an ill-considered purchase of an old economy business. They are not that dumb.

Monday, 19 May 2014

Bowie's takedown of Hadfield's ISS "Space Oddity" highlights copyright's absurdity

by Cory Doctorow at 4:00 pm Sun, May 18, 2014

Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield's cover of Bowie's Space Oddity was a worldwide hit, and now it has been disappeared from the Internet, thanks to a copyright claim from David Bowie. Ironically, if Hadfield had recorded the song and sold it on CD or as an MP3, there would have been no need for him to get a license from Bowie, and no way for Bowie to remove it, because there's a compulsory license for cover songs that sets out how much the performer has to pay the songwriter for each copy sold, but does not give the songwriter the power to veto individual covers (that's why Sid Vicious was able to record "My Way").

As Blayne Haggart's Ottawa Citizen editorial points out, it's hard to make a utilitarian argument for copyright that lets musicians determine who can make Youtube videos from their songs, given that covers are such an accepted part of musical practice. As Haggart writes, "Is the world a better place now that this piece of art has officially been scrubbed from existence?"

Sometimes, the law is an ass. And copyright law, as it’s metastasized over 300 years, definitely possesses ass-like qualities.

The Hadfield Space Oddity takedown is the perfect example of how copyright, which is supposed to promote creativity and increase our access to knowledge and culture, all too often ends up doing the exact opposite. Instead, it becomes a way for copyright owners – usually large multinationals, not actual creators – to control what gets created and seen.

Most people lucky enough not to spend every waking moment thinking about copyright may think that’s just fair – it is their stuff, after all. But what this completely understandable, instinctive response misses is that this will to control often ends up being a veto over the future creation of knowledge and culture.

Op-Ed: Bad copyright rules killed Hadfield's Space Oddity [Blayne Haggart/Ottawa Citizen]

[via Boing Boing http://boingboing.net/2014/05/18/bowies-takedown-of-hadfield.html]

Friday, 9 November 2012

Leveson inquiry: bring in new law to curb press excesses, Tories urge PM'

By Patrick Wintour, political editor, The Guardian, Thursday 8 November 2012

Four former cabinet ministers among Conservatives who say newspaper

industry cannot continue to be entirely self-regulated

An influential group of mainstream Tories, including four former cabinet ministers, have opened the door to a limited form of statutory press regulation, warning that proposals being put forward by the newspaper industry "risk being an unstable model destined to fail". The letter, published in the Guardian and signed by 42 MP's and two peers, signals a potential shift in the politics of media regulation because it is the first suggestion that the Conservative party is not going to respond to the Leveson inquiry with a monolithic opposition to legal regulation of the industry. Lord Justice Leveson is due to publish the inquiry's findings at the end of this month and ferocious lobbying of No 10 is under way from both sides in the argument. The signatories believe their letter may show Downing Street that a cross party consensus on media reform is possible at Westminster.

"No one wants our media controlled by the government but, to be credible, any new regulator must be independent of the press as well as from politicians," the letter says. "We are concerned that the current proposal put forward by the newspaper industry would lack independence and risks being an unstable model destined to fail, like previous initiatives over the past 60 years ".

Labour and the Liberal Democrats are likely to support Leveson if he

suggests the newspaper industry cannot continue to be entirely self-regulated.

The letter suggests that David Cameron has greater room for political manoeuvre

at Westminster than thought. Senior cabinet ministers, including the education

secretary Michael Gove and the communities secretary Eric Pickles, oppose any

form of state-backed regulation of the press. George Osborne, the chancellor,

is also reluctant to see any state intervention.

Cameron has been trying to keep his options open, saying the status quo

is not an option and any new formula has to be justifiable to the victims of

phone hacking. But he is under pressure to support a newspaper industry

proposal that would preserve self-regulation and rely on legally enforceable

contracts to bind publishers to the system, including the possibility of fines.

Similar pressure has been applied to the Labour leader, Ed Miliband, but it is

understood he still stands by the evidence he gave to the Leveson inquiry.

Signatories to the Conservative letter include the former foreign

secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind, two former party chairmen Caroline Spelman and

Lord Fowler, as well as the former chief whip Lord Ryder. It is also supported

by a range of Conservative backbench opinion from right-wingers such as Gerald

Howarth, Jesse Norman and Robert Buckland, a joint secretary of the 1922

backbench committee. Supporters also include Cameron's former press secretary

George Eustice, Zac Goldsmith, Andrea Leadsom, Nicholas Soames, and Gavin

Barwell, the parliamentary aide to Gove.

The aim of the letter, according to one of the instigators, is to break

what is described as the siege of Downing Street by the newspaper industry, and

forge a safe passage for the prime minister so he can engage with the Leveson

inquiry recommendations. It was being emphasised that the letter was not

prescriptive, but an attempt to change the tone of the debate, so it is not

dominated by the press or by campaigners against Rupert Murdoch. The

signatories say they "agree with the prime minister that obsessive

argument about the principle of statutory regulation can cloud the

debate". However, they add that forms of statutory regulation in broadcasting

and sensitive professions such as the law have proved workable.

They write: "We should keep some perspective - the introduction of

the Legal Services Board in statute has not compromised the independence of the

legal profession. The Jimmy Savile scandal was exposed by ITV and the

Winterbourne View care home scandal was exposed by the BBC, both of whom are

regulated by the Broadcasting Act.

While no one is suggesting similar laws for newspapers, it is not

credible to suggest that broadcasters such as Sky News, ITV or the BBC have

their agendas dictated by the government of the day."

They call for greater clarity about a future public interest test for

the publication of stories. The "worst excesses of the press have stemmed

from the fact that the public interest test has been too elastic and too often

has meant what editors wanted it to mean. To protect both robust journalism and

the public, it is now essential to establish a single standard for assessing

the public interest test which can be applied independently and

consistently".

The instigators of the letter stressed they were not acting with the

covert agreement of No 10, although officials are now aware of the move. One

source said: "As Conservatives, we are

reluctant regulators and we firmly believe in a free press, and want to help newspapers

survive, but they have to meet us half way. Their refusal to countenance any

kind of statutory change to raise standards is no longer acceptable to the

Conservative party."

The source said they could incorporate some of the proposals put forward

by the industry, led by Lord Hunt and Lord Black, the peers behind proposals

for a beefed-up Press Complaints Commission. One source said the mood in the

party had hardened in recent months claiming what he described as "the

drip, drip of press stories intended to undermine Lord Leveson's inquiry have

not gone down well among some MPs".

Apart from the merits of a form of statutory underpinning to independent

regulation, it was also being suggested that Cameron might find himself in the

uncomfortable position of defending a newspaper industry at a time when

difficult revelations emerge in court cases. A legislative slot has been

reserved for the next parliament, but it is also possible that Leveson will be

asked to give evidence to the culture select committee once his report is

published. It also emerged that Fowler is to set up an all-party media

parliamentary group probably with former newspaper proprietor Lord Hollick.

Saturday, 3 March 2012

Media inquiry calls for single watchdog

By Kylie Simmons

Updated March 02, 2012 21:11:20

An inquiry into Australia's print media has recommended a new council to oversee all news media organisations.

The News Media Council would be government-funded and would regulate print, radio, TV and for the first time, online.

The inquiry was set up in the wake of Britain's phone-hacking scandal.

In September the Federal Government asked former Federal Court justice Ray Finkelstein QC to lead an independent inquiry into the Australian media.

After months of hearings he has released his findings, with his main recommendation to establish the council, setting new journalistic standards for all media.

The council would take away responsibility for news and current affairs from the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), which looks after broadcasting, and it would also take away responsibility from the Australian Press Council.

The report found the Press Council suffers from serious structural constraints and that ACMA's complaints-handling processes were "cumbersome and slow".

The new council would also handle complaints by the public when standards are breached and it would have the power to make media organisations publish an apology, a correction or retraction or give a complainant a right to reply.

Support 'quality journalism'

Greens leader Bob Brown played an integral role pushing for the inquiry after the News Of The World hacking scandal broke in the UK.

"What [Justice Finkelstein is] looking at here is not punitive action on the media in terms of fines or imprisonment, but rather remedy of inaccuracies or falsehoods or slander if that occurs to people and they're hurt by it," Senator Brown said.

"And I think the public will be right behind that. The best way to do that is to require news outlets where they've made a mistake to remedy it.

"I think that we have an inadequate system of serving the public interest and truth, which are the two first things mentioned in the journalist code of ethics in this country at the moment, and I think this is a big step towards fulfilling the journalists' code of ethics and making sure that quality journalism is supported."

Press Council chairman Professor Julian Disney says its future is now in the hands of publishers.

"I think the problem that Mr Finkelstein faced is that he understandably felt that at least some of the publishers were not willing to provide the extra resources and other support that we need to be able to perform effectively," he said.

"I think it's clear from the report that is really the main reason why he then went for another approach and I think that clearly lays down a challenge now for the publishers.

"Do they want to avoid the kind of body he proposes, which is created by government and entirely funded by government and has quite some risks of excessive legalism?

"If they do, then they're going to have to provide more resources and more support and accept that we need some firmer powers. So really the ball is now in their court."

Conroy meeting

Conroy meeting

Key publishers are planning to meet Communications Minister Stephen Conroy in the coming weeks.

Senator Conroy has released a statement saying the recommendations will be considered but no action is likely to be taken until a wider review of the media is completed later this month.

The convergence inquiry is examining a range of regulatory issues across broadcasting, radio and telecommunications.

Opposition communication spokesman Malcolm Turnbull says a News Media Council does not appeal to the Coalition.

"The segment of the media that is most criticised for lacking in accuracy in balance is commercial talkback radio, but it is regulated by ACMA," he said.

"Metropolitan newspapers, on the other hand, are generally regarded as being doing better in terms of accuracy and balance and yet they are completely unregulated.

"So I think those observations, most people would agree with. Why would your conclusion from that be that the way to get more balance and accuracy is to have more regulation?"

Fairfax media issued a statement saying it is pleased the report acknowledges upfront the importance of a free press in a democratic society and that regulation should not endanger that role.

Like many other media organisations, Fairfax is going through the 474-page report and any further comments will be made in the coming days.

Topics: media, industry, business-economics-and-finance, print-media, federal-government, government-and-politics, australia

First posted March 02, 2012 15:19:18

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)